CIC-symposium "Capreolus" in Salzburg, April 1992 (in prep.).

by

Mogens Ring Petersen

Botanical Institute, Department of Plant Ecology,

University of Copenhagen,

Øster Farimagsgade 2 D, DK-1353 Copenhagen K, Denmark.

and

Helmuth Strandgaard

Ministry of the Environment, National Environmental

Research Institute, Department of Wildlife Ecology, Kalø,

Grenåvej 12, DK-8410 Rønde, Denmark.

Abstract

Roe deer food selection was examined in 7 different Danish biotopes from analyses of the contents of 1745 rumens. In general roe deer fed on a wide variety of plant species. Food choice varied considerably throughout the year and some plant species vary seasonally in importance. (Petersen & Strandgaard 1992).

The European roe deer Capreolus c. capreolus is found in widely different types of biotope. This indicates that the food supply, and thus the food selection, may vary a lot from one locality to another. To clarify this connection the rumen contents of l,745 Danish roe deer from different biotopes have been analysed. The present paper deals with two main locations: Kalø and Borris. While Kalø is a typical Danish deciduous forest, Borris makes out moorland transversed by a river valley. The examinations of the rumen contents showed a clear connection between the vegetation and the food selection. In general roe deer feed on a great variety of plants, and seasonally single species may be of vital importance. In Kalø Anemone nemorosa makes up to half the total intake during winter and spring. In Borris Calluna vulgaris is correspondingly the main winter food. The food selection reflects the animal's need for a versatile biotope with many different plant species all seasons. Full understanding of the roe deer's food selection will not be obtained before the results from the rumen investigations are compared with the observations of the deer's whereabouts.

Keywords: capreolus, rumen content, vegetation.

Introduction

The European roe deer Capreolus c. c. is found in all European countries except Ireland, and in large parts of Asia Minor. Geographically, the range stretches from the Ural and Iran in the east to the Atlantic in the west, and from northern Scandinavia to the Mediterranean Sea and northern Iran in the south (Whitehead 1972).

Not only is the range huge, it also covers widely different types of landscape, ranging from boreal conifer forests to deciduous forests and agricultural areas. This indicates that the food supply, and thus the food selection, may be widely different form one part of the range to the other, and that the roe deer therefore must be able to adapt their foraging strategy to the possibilities within different types of biotope.

Indeed, a series of food analyses from different countries indicate that this may well be the case.

To allow a more specific estimate of the biotope's importance for the survival of roe deer, and of how they utilize the possibilities of the different biotopes, it is necessary to study the food selection in more detail, including seasonal variation in vegetation and in the requirements of the deer.

In Denmark, the rumen contents of 1,745 roe deer from 7 different localities have been analysed. However, the present paper will deal only with the preliminary results of two main locations: Kalø and Borris.

Although Denmark is only a small country (43,000 km2), these two localities may well be considered as exponents of rather different types of landscape.

Kalø is an eastern Danish deciduous forest, where the present-day landscape is a mosaic of woodlands, hedges and farmland. The survey area covers approximately 1,000 ha, constituted with 350 ha woodland and 650 ha farmland with hedges and small biotopes in the shape of coverts. Kalø is a moraine formation with chiefly fertile clay soil. The land is cultivated with mainly corn (wheat and barley), rape, beets and seed grass. Also grass fields and permanent meadows are found. The forest is chiefly deciduous with beech (50%), other deciduous trees (20%) and conifers (30%). The locality has a roe deer population of about 200.

Borris, a western Jutland moorland and plantation area, covers almost 5,000 ha. The locality is a moorland plain landscape traversed by a considerable river valley (250 ha), the Ådalen. The soil is chiefly sand with small nutritive content and a poor water balance. The present-day landscape is a mixture of conifer plantations (approximately 600 ha), willow scrubs (approximately 800 ha), heather moors (approximately 2,500 ha) and grassy plains, including wetlands, (approximately 1,800 ha). A considerable part of the grassy plains is formerly cultivated land. The area has a roe deer population of about 1,000.

In both localities, the population size is first of all a result of the roe deer's own population regulating mechanisms, with emigration of surplus roe deer as the major regulating factor (Strandgaard 1972). Hunting is kept at a level that does not influence the size of the populations.

Roe deer's food selection in Kalø

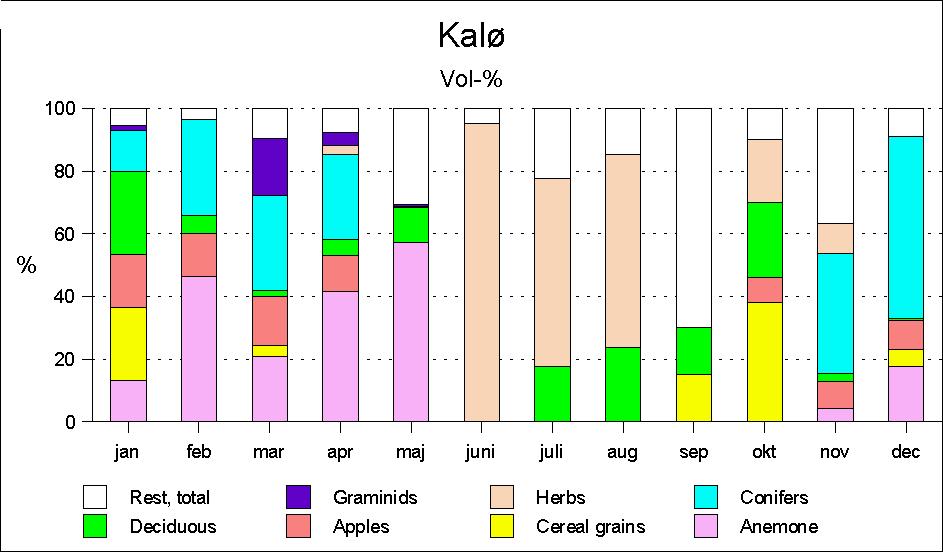

During the summer months of June, July and August, the food intake consists mainly of herbs (Fig. 1) such as Oxalis acetosella, Galium odoratum, Asteraceae, Rumex sp., Stellaria media, Geranium sp., Galium sp., Polygonum sp., Viola sp. etc., i.e. species which the deer may find in the forest as well as in the fields surrounding the forest. Leaves of deciduous trees, particularly hawthorn, beech and willow, are found in moderate quantities in July.

In autumn, different herbs are still of some importance, but from September and particularly October, typical farm crops such as beets gain increasing importance. At the same time the importance of browse as food begins show.

In November the occurrence of browse from deciduous trees decreases abruptly, to fail completely in December, but then conifer browse are found in considerable quantities. During winter the food is composed mainly of conifer browse and farm crops. The latter is mainly fruit plantation windfalls, discarded apples laid out in the forest from fruit stores, beets which the roe deer find in clamps, and corn found in feeding places and in traps.

The deciduous browse found in rumen samples during the winter months is taken to originate from trees made accessible during winter logging.

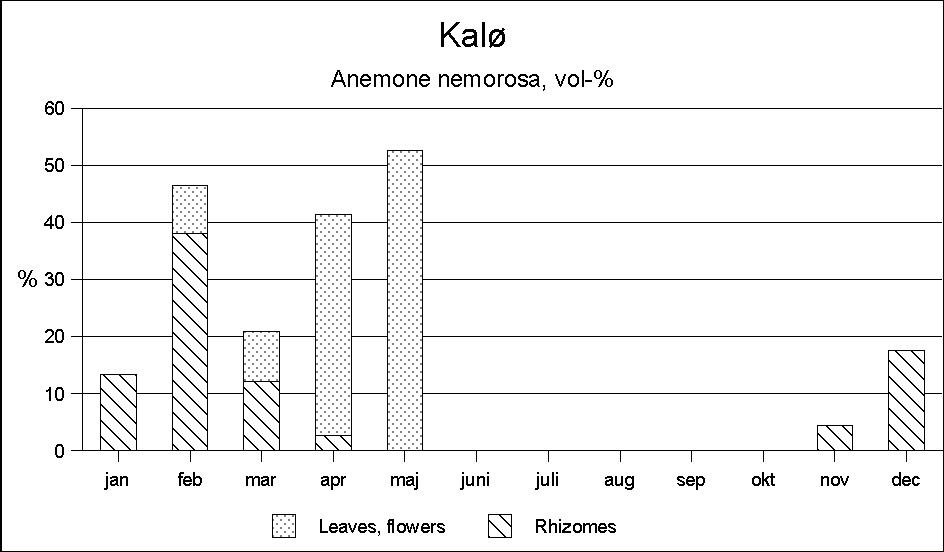

During the spring months, Anemone nemorosa is the main food in Kalø. Furthermore, it should be mentioned that graminids play a certain role in March, and partly April. Observations indicate that the roe deer particularly look for tussock grass.

Altogether, a fairly clear picture emerges of the roe deer's food selection in a deciduous area as Kalø. During summer, the deer are mainly found in the fields surrounding the forest, where they forage on a series of different herbs. During early autumn, farm crops and deciduous browse become the main food. In late autumn, farm crops still play an important role, though now in the shape of beets from clamps and corn from feeding places (traps and pheasant feeding places). The occurrence of deciduous browse ceases abruptly in November, and at the same time conifer browse begins to make up an important element. In late winter, Anemone nemorosa is the most important single species.

Roe deer's food selection in Borris

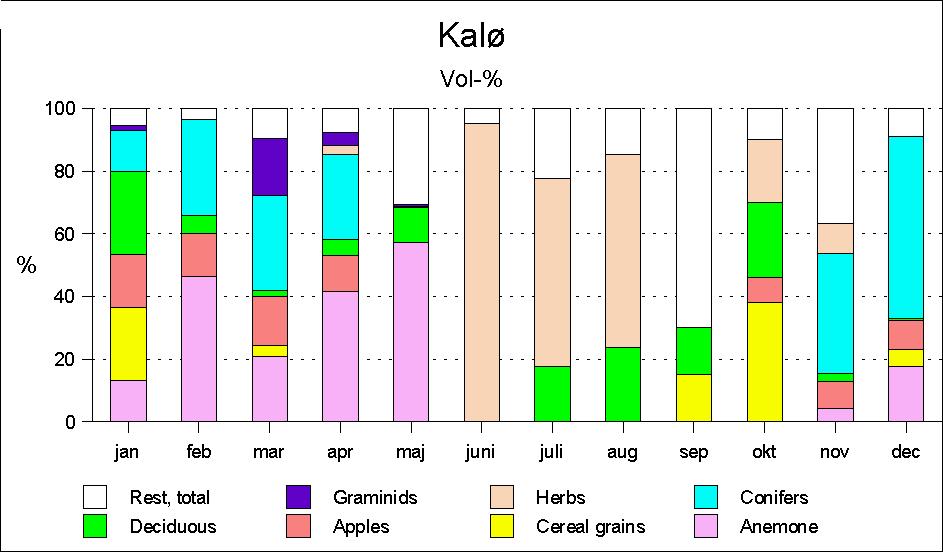

The food choice in Borris (Fig. 2) is significantly different from that in Kalø. As early as May, the pattern of what may be called summer food begins to take shape. Herbs, including woodrush Luzula sp., become the main food, but also graminids are eaten in considerable quantities, particularly at the beginning of the summer. Leaves from willow and heather (Calluna vulgaris) are also eaten, though in smaller quantities.

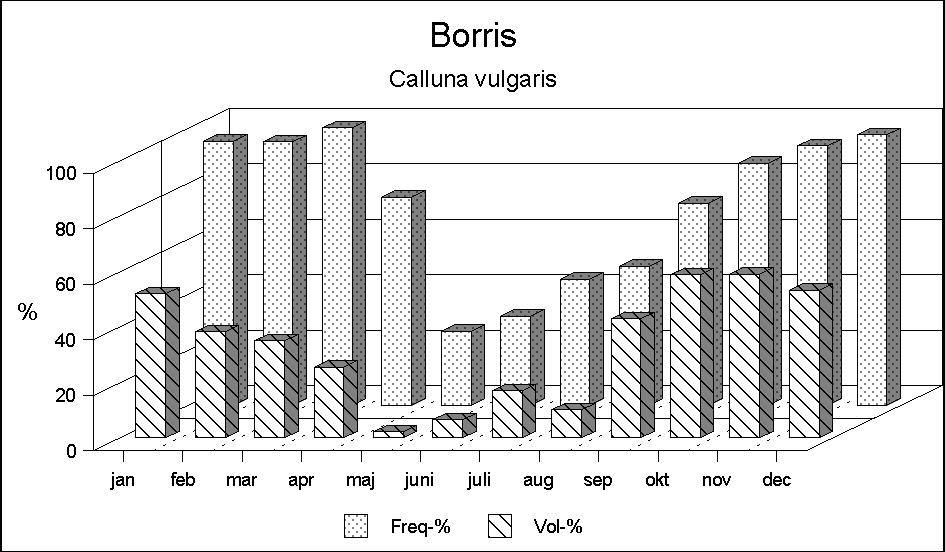

From September, a significant increase in the occurrence of Calluna takes place, and during autumn and winter Calluna is still the main food. During the winter months browse of different dwarf shrubs, particularly bog myrtle (Myrica gale), and farm crops such as corn are also found in the rumen samples, especially in February and March.

In early spring, the occurrence of Calluna decreases, whereas graminids increase; in April the deer begin to find increasing quantities of different herbs.

Discussion

1) A full understanding of roe deer's foraging pattern and the vegetation's importance for their habits will only be obtained when results from rumen analyses can be related to the large number of observations made of the deer's activity in the two localities. Studies based only on rumen contents will hardly suffice to provide a complete picture of roe deer's food selection, or of the way they utilize the different elements of the landscape, i.e. wood types, moors, bogs and farm crops, unless the number of samples is extremely high.

2) In fact, the individual rumen samples only show what the deer ate during a short time lapse immediately before the sample was taken. Accident and individual differences seem to play an important role. For instance, beets have only been found in a few of the Kalø samples, despite the fact that during observations it turned out that roe deer eat large quantities of beets. In August-September the deer often stay in beet fields where they mainly forage on beet leaves, and during winter, observations show that beet clamps are an important element when roe deer select their feeding habitat.

3) Nevertheless, analyses of rumen contents do provide a good background for understanding roe deer's dependence on and adaptation to the habitat.

For the two localities, the food choice as found in the rumen contents shows roe deer's need for a balanced biotope. The fact that both biotopes contain different landscape elements with different vegetation is the reason why the deer's food requirements are met. Through seasonal variation in the utilization of the individual elements, the deer's requirements are covered to an extent which is consistent with the number of individuals that the biotope in question may sustain on a yearly basis.

The distribution of the foods only confirms this theory. Approximately 150 different plant species were registered in the 1,745 samples of rumen contents from roe deer. This means that roe deer utilize a considerable part of the vegetation found in the habitat, but this does not exclude the possibility that some plant species are more important than others. This is owed to two important factors: the accessibility of the plants, i.e. range and seasonal cycle, and the deer's selection of or taste for certain plants or parts of plants.

To some extent, differences and similarities between the two localities may further elucidate this fact. Herbs of a series of different species are the favourite foods in both localities during the summer months. However, in Kalø herbs constitute a much larger part of the food intake than in Borris. This is in agreement with differences in the vegetation of the biotopes. The production of herbaceous plants is smaller in Borris and, considering that the roe deer of that locality forage on graminids to a larger extent during summer, it may be assumed that the reason is that the herb production is insufficient to satisfy the requirements. Furthermore, taking a closer look at what parts of the landscapes the roe deer utilize most in the summer months, it is seen that in Borris, the river valley and other wetlands are selected, i.e. the areas with the most abundant herb vegetation.

Similarly, in Kalø the areas outside the forest are mainly utilized for foraging in the summer months. Neither the dry sandy soil of Borris, nor the overshadowed forest floor of Kalø produce foods in the summer months.

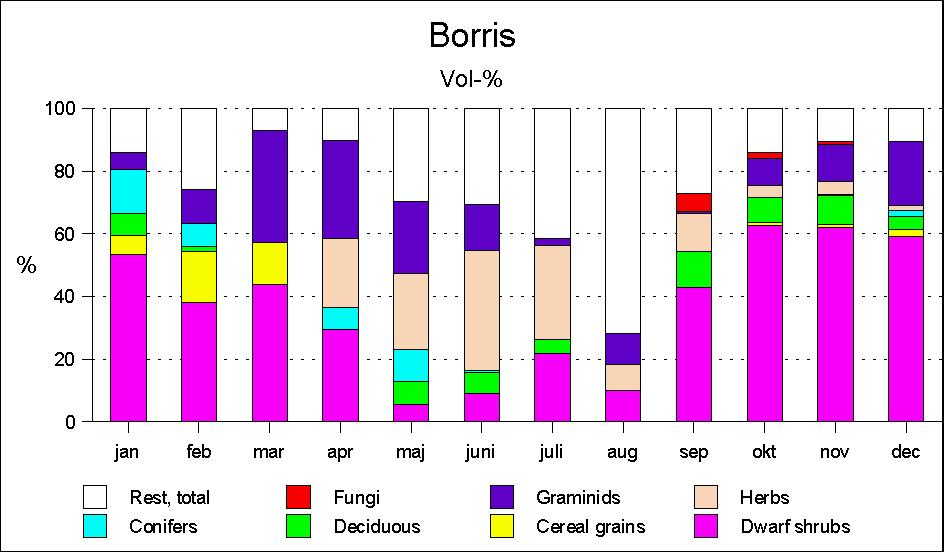

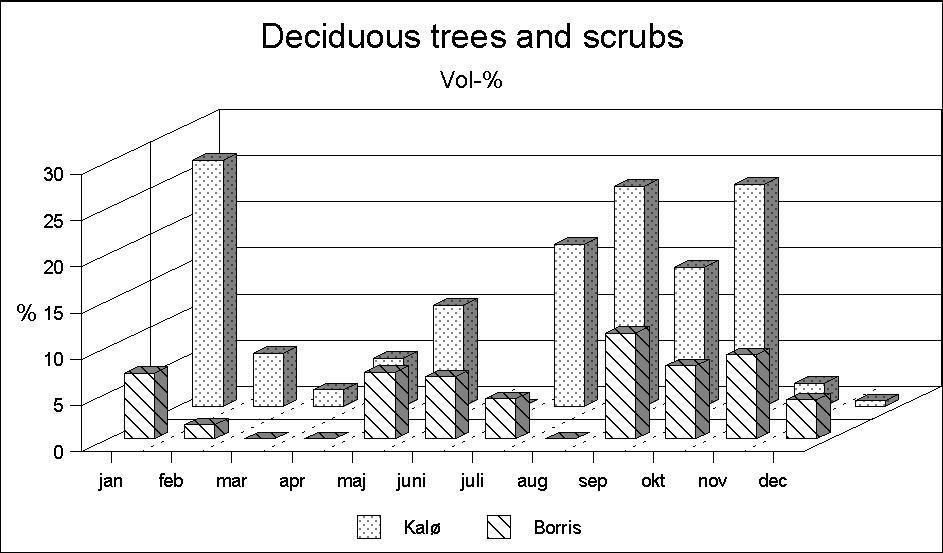

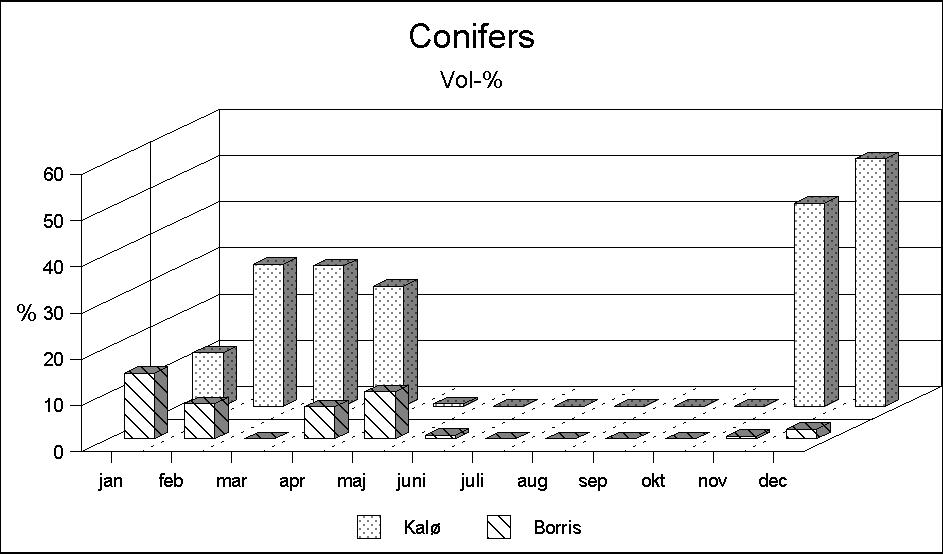

Another interesting difference is the occurrence of deciduous browse in the rumen samples (Fig. 3). During the summer months deciduous leaves are found in the samples of both localities. In Borris chiefly in the shape of willow leaves, and in Kalø of beech (and willow) leaves. However, in early autumn, large quantities of deciduous browse are only found in the Kalø deer. A possible explanation is differences in the occurrence of deciduous species. In Borris, species such as oak, ash and beech are found only in small numbers, and mainly as older oak shrubs of a height that does not allow the roe deer to reach the browse. A corresponding explanation for the occurrence of conifer browse cannot be given. Although accessible conifers are found in the Borris biotope in much larger numbers, this food occurs only in small quantities in deer from Borris, while in Kalø they make up a considerable part of the food intake in November-April (Fig. 4). A possible explanation may be that conifers are not a particularly attractive food.

Preliminary analyses of observations of the deer's whereabouts in the landscape during the autumn and winter months confirm this theory. During the winter months the Borris deer are mostly seen in moorland with heather vegetation. This is in agreement with the fact that Calluna is the predominant food in the rumen samples at that time of the year.

The Kalø deer increasingly stay in the forested part of the landscape from early autumn. Although herbs and farm crops are still important foods, the autumn implies radical changes as a consequence of e.g. harvest and ploughing in the cultivated land. Another factor which may be expected to influence the foraging pattern of the roe deer is the influence of night frost on the herbaceous vegetation. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that browse makes up an increasing part of the food intake. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that deciduous browse is only found in large quantities during September-October. The only possible explanation is that the roe deer simply ate all the accessible quantity during these two months, and that ensuing, lack of sufficient quantities of alternative foods forces them to forage on conifers. A certain occurrence of deciduous trees in February is owed to foraging on cut trees.

Furthermore, it is characteristic for both localities that in some seasons a single plant community may play an absolutely predominant role. In Kalø the importance of Anemone nemorosa (Fig. 5) in the total food intake during the spring months may make this single species to be crucial for the deer's surviving the winter. Anemone is found all the year round, except for August, September and October, but only in February-May it occurs in sufficient quantities to be of nutritive importance. During winter only the subterranean parts of the plants are found in the rumen samples; however, as early as February the Anemone begins to produce new shoots, and in the following months rhizomes as well as flowers and leaves are eaten (Fig. 2) in quantities which make Anemone the most important food in April and May. However, it should be stressed that Anemone is a food of relatively poor nutritive value. The situation may well be that the deer only eat this species in such large quantities out of lack of anything better.

In Borris Calluna is a predominant food (Fig. 6); it is eaten in all seasons, though in strongly varying quantities. During October-April it is present in the rumen contents of almost all deer examined, and it may constitute up to half of the food volume. Finally graminids should be mentioned. In Kalø graminids are eaten only in limited quantities except for early spring, where it may constitute up to 1/5 of the food intake. Observations of foraging deer have shown that they mainly eat tussock grass. The deer seek the sparse new shoots within apparently dry tussocks. In Borris, however, graminids are a food eaten all around the year, and, particularly in spring, they constitute a significant part of the food intake.

During spring the Borris deer chiefly forage on formerly cultivated land, where herbs and a mixture of wild and cultivated grass are found. In Borris these parts of the biotope are situated where new, fresh sprouts are found at the beginning of the year.

To a large extent, differences in the food selection of the Kalø and Borris populations may be ascribed to the variations in vegetation due to different climate and soil. In both localities the general picture seems to be that the roe deer adapt to the possibilities within their ranges. However, these preliminary analyses provide strong indications that roe deer only survive in large populations as a result of the possibilities the areas provide to alternate throughout the year between the different landscape elements found within the areas.

Borris may sustain a large population of roe deer owing to the fact that, apart from plantations providing cover, the biotope contains three important types of landscape; the river valley and other wetlands, the moorland areas, and the formerly cultivated land which are now left as grassy plains. Similarly, Kalø may sustain a large population owing to the deer's opportunities to alternate between the forest and the surrounding fields.

It is yet too early to say to which extent the roe deer utilize the available food resources. However, particularly for Kalø, the deer tend to utilize some food resources fully, after which they are forced to forage on other, less attractive foods.

Although the roe deer's social behaviour limits the population size (Strandgaard 1972), analyses of the food selection indicate that particularly the Kalø population is close to a maximum utilization of the food resources during the winter months.

Related to practical management this provides three possibilities to improve conditions.

On a large scale, improvements will require that, when planning the landscapes, a suitable distribution of the individual landscape elements is aimed at, that variation in the landscape is provided for, and that it is ensured that the roe deer may utilize the area and alternate from one part to the other freely. In plantation areas, open moorland areas should be preserved rather than large, connected conifer areas.

More specifically, one may have to consider a more direct management, e.g. planning logging in the forest so that the deer's favourite species (oak, ash, Abies sp.) are not cut until January-February.

In biotopes with less seasonal variation, however, the practise of supplementary feeding may be more doubtful. When judging from the Kalø deer's food selection during the winter months, access to beets and barley and wheatgrains seem to be of some importance. Both feeds may easily be supplied, but at the same time the question arises whether winter feeding of roe deer in that type of biotopes may contribute further to an unbalance between the biotope and population size.

Further analysis of the relations between food selection on the background of rumen samples and observation of the roe deer's geographic distribution in the areas, and thus regulation of numbers, will elucidate these aspects in more detail.

References

Strandgaard, H. (1972): The roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) population at Kalø and the factors regulating its size. Danish Review of Game Biology, Vol. 7, no. 1.

Whitehead, G.K.N. (1972): Deer of the World. London: Constable.

Figure 1: Seasonal diet of roe deer in the Kalø areas by rumen content analyses.

Figure 2: Seasonal diet of roe deer in the Borris areas by rumen content analyses.

Figure 3: Deciduous browse makes up a larger part of the diet in Kaø than in Borris. This is in accordance with the differences in the biotopes.

Figure 4: Conifer browse makes up a larger part of the Kalø deer's diet, although conifers are more accessible in Borris.

Figure 5: As a single species Anemone nemorosa is the most important herb in Kalø in winter and spring.

Figure 6: Calluna vulgaris is taken all the year round in Borris. Except in summer it is the most important part of the diet of the Borris deer.